Strategies for Rural Development in Areas with Limited Public Infrastructure: Alternative Septic Systems

Strategies for Rural Development in Areas with Limited Public Infrastructure: Alternative Septic Systems

What is a decentralized waste water system?

What is a Decentralized Waste Water System?

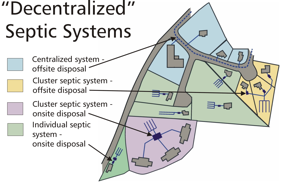

A decentralized system for wastewater management may include one or several types of wastewater treatment, but it is important (and state-mandated) that all the system components have a centralized administration and management program. Decentralized systems can include traditional onsite septic systems that serve individual homes or businesses (shown in green on Figure 1 below). They can also include larger septic systems that serve clusters of homes, subdivisions, apartment buildings, or businesses. These shared systems may serve multiple buildings on a single property (shown in purple) or may serve several different properties (shown in tan). Finally, centralized disposal systems with off-site collection pipes, treatment, and eventual soil-based dispersal may be included within a decentralized wastewater system (shown in blue). These systems can be especially useful in villages with very small lot sizes, or in areas with valuable natural resources that need to be protected from potential wastewater contamination.

FIGURE 1: Disposal alternatives within a decentralized septic system

Similarly, decentralized drinking water systems can include a mix of individual onsite drilled wells, and shared or community water supplies (particularly useful for compact developments). Public water supply wells require large buffer areas for protection, and should be planned and sited early in the development process.

Components of a septic system

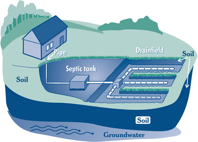

Conventional onsite septic systems include a 1000-gallon septic tank, a distribution box, and disposal field, also known as a leach field, as shown in Figure 2 below. The septic tank settles out solids and greases, and provides some treatment. The wastewater effluent then flows through a distribution box where it is evenly divided among several perforated pipes, discharging into stone trenches or beds. Raised systems such as mounds include sand fill, which provides the necessary separation between the disposal system and seasonal groundwater or shallow bedrock. Mounds are pressurized with a pump, which evenly distributes the waste water throughout the disposal field.

FIGURE 2: Components of a septic system

Pre-treatment systems

Pre-treatment systems provide an additional preliminary process (or multiple processes) for filtering and waste decomposition before the treated effluent is allowed to flow into the disposal field. These systems are often used to improve treatment performance standards in poorly draining soils. They can help a system with heavy organic or toxic loading achieve its desired performance goals, and neutralize environmentally harmful nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. The use of pre-treatment technologies can usually reduce the total land area needed for a disposal field, typically by about 50 percent. On some sites, pre-treatment may allow for the use of a subsurface disposal field instead of a more expensive raised mound.

Pre-treatment systems can also be used to retrofit commercial establishments with heavy organic loading characteristics, so they can discharge the pre-treated effluent to an existing community leach field or public sewer without disrupting the existing treatment processes (or violating state and federal wastewater standards). In many cases, the effluent emerging from a pre-treatment system will be almost as pure as drinking water when it enters the public sewer or leach field, thus actually improving the overall quality of the combined effluent flow through dilution. The Town of Milbridge used pre-treatment systems to allow commercial facilities with high organic and suspended solids content in their effluent to continue to use the public sewer system, thus avoiding the need for costly secondary treatment system upgrades to its wastewater treatment plant; for more information on this project, click here.

Disposal fields

Disposal fields, also known as leach fields, are typically constructed with perforated PVC pipe placed in stone aggregate, which is then covered with filter fabric and topsoil. Alternatives include pre-fabricated concrete or plastic chambers, engineered peat systems, and subsurface drip disposal methods. The location, size and depth of a disposal system are all determined by the specific soils and site conditions that are identified on the property. Additional considerations for locating a disposal field include the surrounding topography, sensitive environmental features on or near the site, and any required setbacks. Direct leaching to a subsurface disposal field is not permitted in areas where the depth to seasonal high groundwater table or a restrictive layer (such as bedrock or thick clay) is less than seven inches below ground. However, the use of modern pre-treatment systems and innovative design techniques have made it possible to use subsurface disposal methods even in locations with severe site limitations.

Community systems

Community wastewater disposal systems, also known as clustered or shared systems, should be considered in cases where soil conditions, lot size, or topography complicate the placement of individual onsite systems. They can also be used to facilitate compact development with smaller lot sizes and reduced infrastructure costs. Clustered systems can be as simple as a conventional subsurface disposal field shared by two lots and served by individual septic tanks, or as complex as a neighborhood collection, treatment and disposal system that is comparable in size and scope to a small municipal sewer system. Systems larger than 2000 gallons per day are required to be designed and stamped by a Professional Engineer, and require approval from both the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the Division of Environmental Health (DEH) within the Maine Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). As community systems increase in size and complexity, the required treatment performance standards also increase. All shared systems serving three or more lots require the designation of an independent legal entity that will manage the long-term operational and maintenance requirements, so if there is no existing municipal or regional sanitary district that can assume this responsibility, a private, public, or quasi-municipal management authority will need to be established early in the development process.

Related Work Plan Components

- Climate Change and Infrastructure Resilience

- Modernizing Communications/Electric Utility Infrastructure

Workgroup Contacts

In Aroostook County: Jay Kamm, Ken Murchison, Joella Theriault

In Washington County: Judy East

Share this content: